Why did AMD’s random number generator start returning 0x0000?

And why cryptographic randomness matters.

If there’s one thing we love here at Zach’s Tech Blog, it’s weird security vulnerabilities in processors. So when I saw that there was a security flaw in AMD’s Zen 5 processors that made its random seed instruction, RDSEED, start returning far too many zeroes to be truly random, I knew I had to write about it. Plus, it’s a really great excuse to talk about one of my favorite topics in cryptography: why elliptic curve signatures are really hard to implement securely.

Generating true random numbers is really important for cryptography. Some algorithms don’t require particularly special random numbers, but others, like the elliptic curve digital signature algorithm (ECDSA), are incredibly sensitive to the “quality” of their randomness. If you’re using ECDSA, even slight biases in your random numbers can allow attackers to extract your private key, given enough signatures.

What makes a random number generator good enough for cryptography, then? Well, its output should be computationally indistinguishable from truly random numbers. That’s usually measured by standard statistical tests. Usually, the best random number generators are so-called true random number generators, or TRNGs, which use randomness extracted from the environment. But the specific flaw AMD disclosed lay within their implementation of the RDSEED instruction, which is supposed to generate random output using their TRNG. This should be the best source of randomness on the chip, but it suddenly started returning far more zeroes than expected. So what went wrong?

What was wrong with AMD’s TRNG?

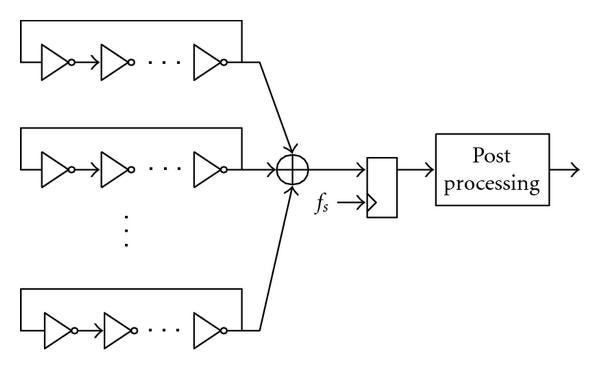

Most TRNGs deployed in modern CPUs use some form of analog noise on the chip to generate truly random numbers. While AMD hasn’t publicly confirmed their TRNG’s randomness source, it’s most likely based on free-running ring oscillators. The frequency of free-running ring oscillators changes randomly based on temperature, jitter, power supply noise, and all other sorts of random environmental factors. If you sample the state of that oscillator with your much-more-stable system clock, you can generate random bits.

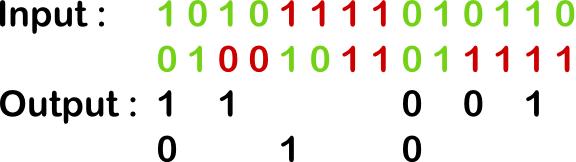

Unfortunately, the bitstream you generate from your ring oscillator is often biased in some way -- a specific chip may randomly sample more ones than zeroes, simply due to the process variation on that piece of silicon. So it’s common to use some form of randomness extraction, conditioning, and whitening algorithms to post-process your raw random bits into a set of uncorrelated random bits suitable for use in a cryptographic algorithm. Modern cryptographic TRNGs usually use a combination of Von Neumann conditioning and hash based conditioning to post-process their random source.

The Von Neumann conditioning algorithm is particularly simple and clever -- it groups output bits two-by-two, discards any pair where the bits are the same, and converts 01 into 0 and 10 into 1. This removes simple biases from the raw bitstream:

One big problem with this TRNG architecture is that it’s just a bit slow. Multiple ring oscillators are combined to return one raw random bit per cycle. The Von Neumann conditioning algorithm ends up discarding more than half of those bits to remove bias. Then, bits need to pass through a cryptographic hash function for additional post-processing before they can actually be used.

Because of this, modern CPUs don’t generate randomness on-demand, whenever a user invokes the RDSEED — it would be too slow. Instead, CPUs are constantly generating random numbers and storing them in a buffer, which the RDSEED instruction fetches random numbers from. But this means that, if a user invokes RDSEED too often, the buffer can run out of random numbers. In that case, the instruction is supposed to return with its carry flag, CF, set to 0, which indicates to software that the randomness buffer was not ready and that it should try again.

The issue with AMD’s Zen5 processors is that, for the 16-bit and 32-bit versions of the RDSEED instruction, CF gets set to 1 even if the randomness buffer is empty. And when the randomness buffer is empty, it returns zero, rather than a real random value.

But wait -- is it really that bad if a TRNG returns zero slightly more than it should? Well, it turns out that it can actually be extremely bad. In fact, even slight biases in random numbers can be catastrophic.

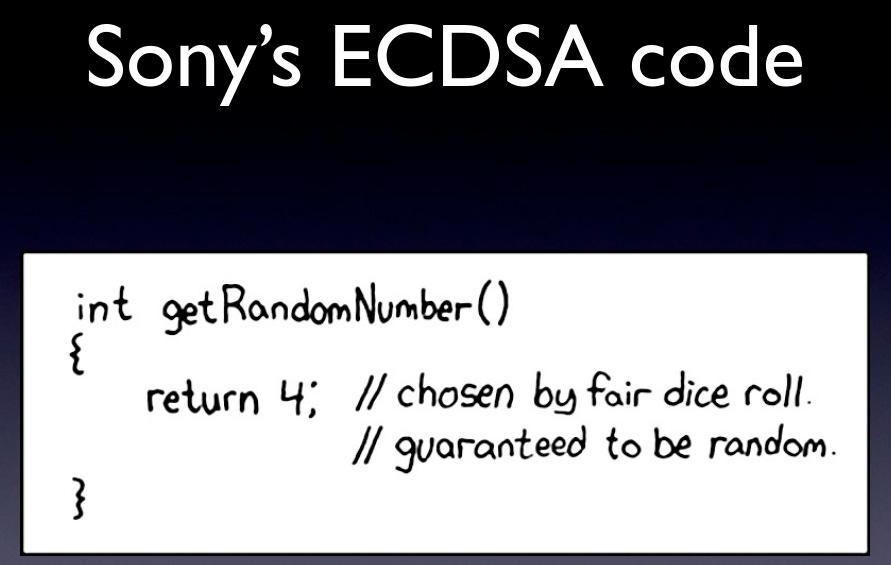

ECDSA and the PlayStation 3

Elliptic curve cryptography (ECC) replaced the RSA cryptosystem in the mid-2000s because of its ability to provide similar security levels with much smaller keys: a 256-bit ECDSA key has comparable security to a 3072-bit RSA key. However, RSA-based signatures had one major advantage over the elliptic curve digital signature algorithm (ECDSA). Performing an ECDSA signature requires generating an ephemeral random number called a nonce. If that nonce is reused, attackers can easily determine the private signing key, as they famously did to extract the signing key for the PlayStation3.

Luckily, it’s pretty easy to avoid making this specific implementation mistake. Unfortunately, even if you change the nonce with every signature, slight biases in the RNG used to generate the nonce will still leak the private key! Each time an ECDSA key is used to generate a signature, if the nonce is biased, it leaks some information about that key; with enough signatures, an attacker can reconstruct the key. This happened in the real world when maintainers of the Debian-specific fork of the OpenSSL package modified their PRNG in a way that (hopefully accidentally) introduced significant bias. If a software developer was using AMD’s RDSEED instruction to generate ECDSA nonces, they could end up signing multiple messages with a nonce of zero, or a nonce biased towards containing more zero bits in it, and compromising their private keys.

Thankfully, there are ways to work around the TRNG bug in AMD’s chips. The 64-bit version of RDSEED isn’t affected, so software developers can just use that instruction without concern. But it’s an interesting lesson in how TRNGs work and the ways very minor bugs can cause very major security flaws when they’re integrated into a full system.

Stellar write-up on the RDSEED bug. The PS3 example really drives home how catastrophic nonce reuse is for ECDSA, but the subtler angle about bias slowly leaking bits over many signatures is way scarier imo. Back when I was messing around with crypto implementations, I never fully appreciated how sensititve EC schemes are to RNG quality compared to somthing like RSA. Makes you wonder how many embedded devices are out there with similarly flawed TRNGs nobody's caught yet.